Chapter 7: A Midnight Call

Larry has been staying with Allen for about a week and a half at this point. Larry’s mom, Amelia has started going to AA meetings and her and Larry’s relationship is beginning to improve. Larry will soon be starting back at college and will move into the dormitory at that point.

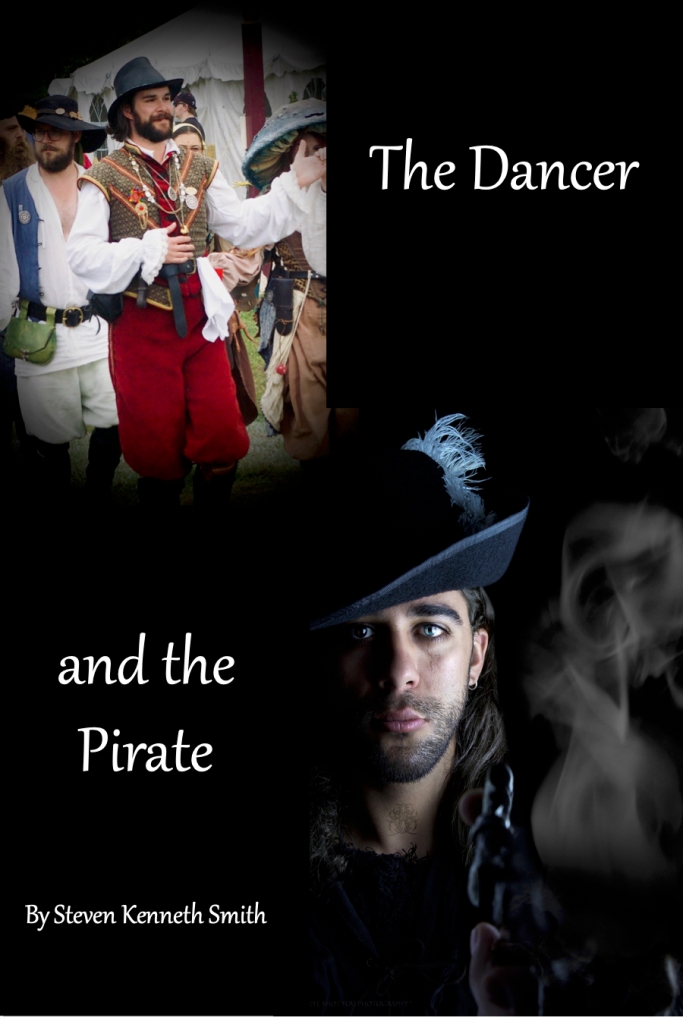

You can check out the book on Amazon from the link below.

amazon.com/author/www.sksmithwriter.com

Tuesday night Allen came home to find Larry had outdone himself for dinner. Herbed, roasted chicken breasts, baked sweet potatoes, and broccoli spears dusted with grated parmesan. A pie sat on the counter. Allen raised his eyebrows. “You baked a pie, too?”

“I got the pie at the supermarket. It’s apple. I hope you like that kind.”

“Yeah. Apple is great. This is quite a surprise.” He shot a glance to the table. Larry had set out candles this time. “What’s the occasion?”

Larry cut open the sweet potatoes and added butter. “A couple of things. Got a call from Mom, and she’s still doing well, at least as far as I can tell. She sounded good. And I got notice that my application for a room in the honors dorm was approved.”

“That’s awesome, Larry. On both counts.”

Larry set two plates to the table and lit the candles. “Dinner is served.”

“Okay, thanks. Uh—I need to wash up. I’ll be right back.” As he went down the hall to the bathroom the thought hit him full force that Larry would be leaving soon. Of course, he knew that, but he’d gotten used to him being here, and he liked being with him. And Larry was a better cook than he.

While he soaped his hands it occurred to him that this was the first time he could remember that his initial thoughts regarding one of his contacts wasn’t about sex.

***

Larry fell asleep right after they’d made love that evening, even though it was still early. Allen had been submissive, but responsive, just as he liked, and he tried to be attentive to Allen’s needs as well. Allen’s happy cries as they coupled encouraged him that he’d succeeded. After they disengaged he kissed Allen, and his response to his kiss gave him every confidence that he’d satisfied him. They drifted off to sleep in each other’s arms.

Some time later his phone rang. He checked Allen’s clock-radio. 11:32.

Allen stirred as Larry swung out of bed and found his phone in the pile of his clothes on the floor. It had gone to voice-mail by that time. The caller ID said, “Mt Sinai Hospital ER.” Oh shit. He hit the “Call Back” button on the screen. A couple of seconds passed. Then: “Hello, emergency room desk.”

“This is this Larry Johnson, returning your call.”

“Just a moment.—Is your mother’s name Amelia Johnson?”

An icicle stabbed his heart. He sat down on the edge of the bed. “Yes.”

“Your mother was just admitted to the emergency room. She was in an automobile accident and is in serious condition. You should get here as soon as possible.”

“Oh my God!”

Allen bolted upright behind him.

“I’ll be there as soon as I can,” Larry said. “Was she—” He gulped. “—Was she drinking?”

“I don’t have that information. The doctor will fill you in when you get here. Come in through the Emergency Room entrance and check in at the desk. Mt. Sinai Hospital, 350 West Main Street, in Clairsville.”

“Yeah. Right.” Larry disconnected and slid out of bed. He searched in the darkness for his clothes. “Shit, oh shit, goddammit, shit.”

Allen crawled across the bed and turned on the light. “What happened?”

“Mom was in a car wreck and is in the hospital in Clairsville. Mt. Sinai ER. They need me there now. Goddammit, I’m fucking two hours away!” Larry had the wrong foot in his pants leg. He kicked it out and tried again.

“I know where that is,” Allen said. “I’ll drive you. My car’s more reliable.” He slid out of bed and pulled on his trousers.

***

Allen crowded the speed limit by 5 to 10 miles per hour or more all the way to Clairsville. Larry didn’t speak much, but he fidgeted in his seat beside him the whole way. Allen concentrated on driving. He reflected that before Larry had been staying with him he would have likely had at least two or three drinks under his belt by now. He might have still tried the trip under the circumstances, but he was glad he didn’t have to do it impaired.

They pulled up to the ER entrance at 1:16 by the dashboard clock. Larry said, “Thanks,” and jumped out of the car. He ran into the building without further comment. Allen pulled through the drop-off spot and went to park.

By the time he walked back to the ER from the parking lot Larry was nowhere visible. He looked around a moment, then headed to the reception desk. A middle aged woman with graying black hair looked up at him as he approached.

“May I help you?”

“I’m Allen Stewart, here for Amelia Johnson.”

She consulted her screen. “Her son was just here. Are you a relative?”

“I’m—uh—Larry’s partner.”

“He’s in a consultation room with a social worker. I’ll buzz her. Allen Stewart, you said?”

“Yes.”

Allen expected her to call her on the phone, but instead she typed on her keyboard for a moment and hit the “return” key with a decisive clack of her little finger.

“It might take a little bit before she responds,” the receptionist said, “I’ll call you when she messages me back. Have a seat.”

Allen headed toward the seats in the waiting area, but before he sat the receptionist said, “Mr. Stewart, you can go back.” He turned around and she pointed toward a door in the back of the room. “Consultation room C.”

***

Larry had a box of tissues in his lap and had a couple of them clenched in his fist. He and another woman looked up when he opened the door. Allen laid a hand on Larry’s shoulder. “How is she?”

“She’s in surgery. Lost a lot of blood, and her left leg is badly broken. Complex fracture. They said—” he sniffled and wiped his eyes. “—they said she might lose it.”

“But she’s going to live?”

“Yeah. Probably.” He tilted his head toward the social worker. “They won’t commit to anything.”

“Of course they won’t,” Allen said. “They don’t know enough yet. We have to wait for the surgery to finish, and to see how she heals.”

Larry nodded and wiped his eyes. He shook his head. “All those times she drove drunk and got away with it, and this time she was sober, coming back from an AA meeting, and—and some goddamn drunk ran a red light and T-boned her car.”

Allen sat beside him and gave him a tight hug. “We’ll get through this. It’ll be okay.”

Larry nodded as best he could with his head pressed against Allen’s shoulder, sobbing.

Allen turned to the social worker while still embracing Larry. “How’s the other driver?”

She closed her eyes for a moment and pursed her lips. “I can’t tell you that.”

Allen looked her in the eyes. “He’s dead, isn’t he?”

She closed her eyes again. She shook her head. “I can’t tell you that.”

Allen grimaced and rolled his eyes. “Yeah. I understand. Thanks for letting us know.”

Larry sobbed anew, his face still buried in Allen’s shoulder.

***

It was almost four in the morning when someone came to the surgical waiting room and summoned Larry to another consultation room. Larry had just dropped off to sleep less than an hour earlier but he came awake instantly when Allen tapped his shoulder.

“Your mother’s out of surgery,” the social worker said, a different one than the one they’d seen before. The room she led them to was smaller and more spartanly furnished than the one downstairs, but it had light panels attached to the wall for viewing x-ray films. Allen took the seat farthest from the door and they settled into the molded plastic chairs.

After a couple of minutes a man came in wearing green surgical scrubs dotted with blood stains. His surgical mask hung beneath his chin. Allen and Larry stood. The doctor closed the door behind himself and waved them back down to their seats. He took a seat himself.

“Hi. I’m Dr. Callan. I’m an orthopedic surgeon. Which one of you is Amelia’s son?”

Larry raised his hand. “Me.”

Dr. Callan focused on Allen. “And you are…?”

“Allen Stewart. I’m Larry’s partner.”

Dr. Callan raised an eyebrow and turned back to Larry. “Are you okay with him being here?”

Larry shot a glance to Allen, eyebrows raised, then looked back to Dr. Callan. He nodded. “Yes.”

Dr. Callan lowered his chin momentarily. He pulled the mask off his face and crumpled the green skullcap he wore into his fist. He ran his fingers through his graying hair, and sighed. “Okay. I think she can keep her leg.”

Larry and Allen heaved sighs, but Dr. Callan raised a hand to stop them. “She’s going to have a long period of rehabilitation though. Her femur was broken in multiple places, and she had some extensive soft tissue damage to her thigh muscles. We had to reconnect some blood vessels,and piece her femur—her thigh bone—back together. It’s going to take a while until the bones knit.

“I won’t sugarcoat this, Mr. Johnson. She might eventually decide it’s better to have an artificial leg than the damaged real leg. It’s going to be painful, difficult, and it’s going to take a long time to heal. If it ever does. Even if she does heal there’s almost no chance she’ll regain all of her original function. She’ll always walk with a limp, best case; or she’ll have to use a walker.”

Larry turned to face Allen for a second, then turned back to the doctor. He opened his mouth, but the doctor spoke first.

“You don’t have to make a decision now, and you shouldn’t. What I’ve done so far preserves her prospects going forward. She can make her decision about long term options later.”

Larry nodded, tight-lipped. “Thank you.”

“Aside from her broken leg she has some lacerations on her left arm, her neck, and her face, some of which had to be sutured, but those were relatively minor in comparison. She’ll be in recovery for a while yet, and then they’ll move her to a room. You can see her then, but she’ll be sort of groggy for some time. I also want to prepare you: she’ll look pretty scary, but considering what she’s been through, she’s in good shape.”Dr. Callan stood and clasped Larry’s shoulder. “Best wishes.” He left the room.

Larry turned his face to Allen. He met his eyes for a moment, lowered them, sighed, and lifted his gaze to Allen’s again. “My partner, eh?”

“Larry, I’m sorry. I wanted to support you and I was afraid they wouldn’t—”

Larry pressed his fingers over Allen’s mouth. “It’s okay. I appreciate your support, and I understand why you said that.” He lowered his hand. “I sort of like the idea of being your partner. I hope—” He wiped his eyes “—I hope I can continue being your partner after we leave the hospital.”

Allen wrapped his arms around him. “Of course you can.”

Larry returned his embrace. “Thank you.” He sniffled and wiped his nose with the back of his hand. “Oh God, thank you so much.”